Laws and regulations governing cybersecurity

6. Protection of personal data in cyberspace

6.2. GDPR

The General Data Protection Regulation (EU) 2016/679 or the GDPR [1]is one of the most important international legal documents that is directly related to the issue of cybersecurity, although it is not primarily aimed at the field of ICT.

“GDPR ≠ IT + software.

The new data protection regulation has 778 lines. Only 26 of these directly concern IT security. Do you have any idea what the others contain?”

Mgr. Eva Škorničková[2]

It is the GDPR and the implementation of the obligations arising from this regulation that can be demonstrated by the fact that it is appropriate to comprehensively address security issues and not artificially isolate the obligations arising from various legal norms (in this case the Cyber Security Act and the GDPR).

The aim of this publication is not to perform a separate and comprehensive analysis of GDPR issues. Only partial terms, rights and obligations arising from the GDPR that at the same time have an overlap in the field of cybersecurity will be defined here.

The GDPR Regulation is a general legal framework for the protection of personal data valid and effective throughout the EU and, in certain cases, outside this territory. The main objective of the GDPR is to ensure comprehensive protection of the rights of data subjects against unauthorised treatment of their data and personal data, to strike a balance between the legitimate interests of controllers, processors and data subjects, to create a system of uniform law enforcement and a single sanction mechanism in this area, etc.

The scope of collecting and sharing personal data has increased significantly due to information and communication technologies and services that are linked to them. Information and communication technologies allow both private companies and public authorities to use personal data to an unprecedented extent in carrying out their activities. On the other hand, it is also possible to observe massive voluntary disclosure of personal data by natural persons whose data this applies to.

Information and communication technologies have significantly changed the economy and social life. They should facilitate the free movement of personal data within the European Union and the transfer of such data to third countries and international organisations. At the same time, however, these technologies and the processes associated with them should ensure a high level of protection of personal data.[3]

Due to the above, however, an interesting paradox arises, which consists of the following points:

- natural persons on their own voluntarily publish an ever-increasing amount of data about themselves (photos, videos, etc.), typically using information society services based on EULA[4] or SLA[5] between a user and a service provider to distribute this data,

- personal data are mostly published on social media, which, by the nature of its operation, presupposes such disclosure and enshrines in the Terms of Service the rules on the basis of which such data are treated,

- when using a number of information society services, natural persons assume, and often expect, the interaction between these technologies and their cyber personality[6].

- the international community, state and natural persons themselves demand greater security of personal data and the denial of access to this data to other (usually unauthorised) entities, all provided that the existence of the first three points of this paradox is maintained.

The consequence of this paradox is obvious. Information society service providers[7] must therefore make greater efforts to secure the individual services they provide to the end user, to increase the level of security of user-related data, to modify the existing Terms of Service and to introduce additional requirements arising from the GDPR.

6.2.1. Territorial scope of the GDPR

One might think that a way to avoid the GDPR would be to move beyond its reach, that is, outside the territory of the EU. However, the GDPR applies in cases where:

- a controller or processor is established in the EU, regardless of whether the processing takes place in the EU,

- controllers or processors are not established in the EU, but

- goods or services are offered to data subjects in the EU (regardless of remuneration),

- the conduct of data subjects within the EU is monitored.[8]

Due to the territorial scope thus defined, the GDPR has an extraterritorial impact and will in effect apply to all information society services that can be accessed from the geographical territory of the EU or that monitor the conduct of data subjects within the EU.

6.2.2. Personal data

Pursuant to Article 4 (1) of the GDPR, personal data are “any information relating to an identified or identifiable natural person. An identifiable natural person is one who can be identified, directly or indirectly, in particular by reference to an identifier such as a name, an identification number, location data, an online identifier or to one or more factors specific to the physical, physiological, genetic, mental, economic, cultural or social identity of that natural person.”

According to the GDRP, personal data are any information (e.g. pictorial, written, verbal, digital, genetic, medical, etc.) that is related (by content – e.g. name, address, job title, email, etc.) to a data subject.[9] From this point of view, and in line with the interpretation given in recitals 30, 34, 35 and 38 of the GDPR[10], the following should be considered as personal data:

- name and surname,

- identification number,

- birth certificate number,

- location data (geo-),

- age and date of birth,

- gender,

- personal status,

- citizenship,

- network

identifiers,

- IP address,

- cookie identifiers,

- radio frequency identification tags, etc.,

- photography,

- elements of physical, physiological, genetic, mental, economic, cultural or social identity,

- personal or work address,

- personal or work telephone number,

- personal or work email,

- verification identification data,

- identification numbers issued by the state.

Bold personal data are typically related to information and communication technologies as well as the applications that use those technologies. The expansion of the range of data that can be considered personal data significantly affects the issues of cybersecurity and ensuring the protection of data that is managed in the organisation.

If we focus on the item of network identifiers and authentication identification data, we will find that a number of data enabling the basic functioning of a computer system in a network can and probably will be considered personal data.

There is a question often discussed in practice – is an IP address personal data?

In this case, in addition to the GDPR, it is appropriate to take into account the case law of the Court of Justice of the EU, which ruled, inter alia, in the case: Patrick Breyer versus Federal Republic of Germany.[11]

Patrick Breyer demanded in German courts that Germany stop retaining his IP addresses, which it obtained during his “visits” to several publicly accessible websites of the German federal authorities. From the point of view of the activities of the operators of the websites in question, this was a classic logging of the services offered by this ISP[12].

The German courts stayed the proceedings and referred the question to the EU Court of Justice for a preliminary ruling because there was no uniform interpretation of EU law in the present case.

In particular, it is necessary to proceed from an “objective” or “relative” criterion in order for a single detail to be personal data and thus identify a specific person.

“Objective” criterion means that data such as IP addresses could be considered as personal data processed by ISPs of non-connection services (e.g. by a website operator), even if only a third party would be able to identify a specific user (typically ISP connection).

“Relative” criterion means that IP addresses could be considered personal data for an ISP connection as they allow it to pinpoint the identity of a user, but no longer for ISP services that actually only have IP address information and do not know the visitor’s name.

The Court of Justice of the EU stated that it is indisputable that a dynamic IP address does not constitute information about an “identified person” as the address does not directly reveal the identity of the individual owning the computer from which the website was visited nor the identity of any other person who may have used the computer.

On the other hand, the Court (Second Chamber) also stated (and subsequently ruled) that a dynamic address of an internet protocol held by an online media service provider in connection with a person’s access to a website that was made available by that provider to the public constitutes personal data for that provider within the meaning of Article 2 (a) of Directive 95/46/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 24 October 1995 on the protection of individuals with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data, so long as the provider has legal means at its disposal that enable it to have the data subject identified by means of other information available to that data subject’s internet service provider.

According to this judgment, dated 19 October 2016, a dynamic IP address may in certain circumstances be personal data.

We demonstrate the impact of the fact that an IP address, as well as other network identifiers, can be personal data in two examples.

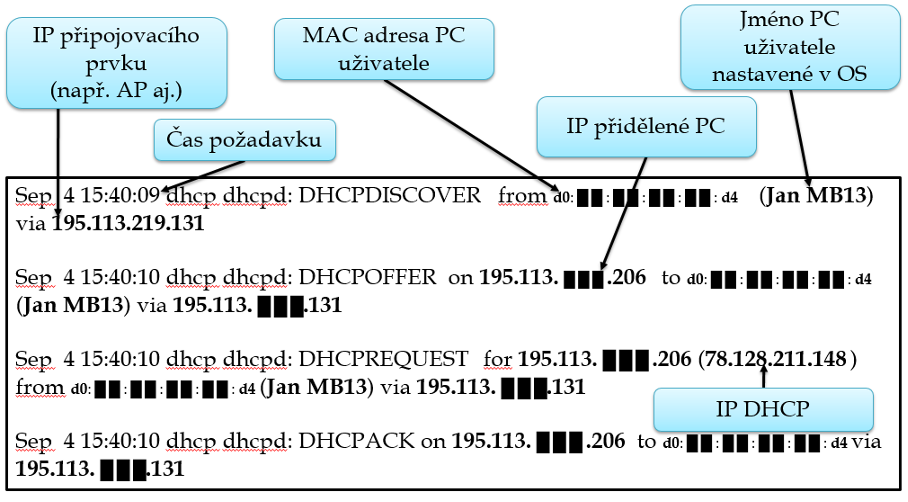

The following figure shows the communication of a PC and individual network elements (AP, DHCP server) and the subsequent connection of the PC to the network.

Figure: DHCP

|

IP připojovacího prvku (např. AP aj.) |

IP of the connecting element (e.g. AP, etc.) |

|

Čas požadavku |

Request time |

|

MAC adresa PC uživatele |

MAC address of the user’s PC |

|

IP přidělené PC |

IP assigned to the PC |

|

Jméno PC uživatele nastavené v OS |

The name of the user’s PC set in the OS |

|

IP DHCP |

DHCP IP |

If we consistently focus on data (information) that are related to the data subject and are able to identify him/her, then personal data in this case will not only be the IP address of the connecting element and the IP address of the DHCP server.

Theoretically, the time of a request is also personal data as it is a trace that can be used to identify a natural person, especially in combination with unique identifiers and other information that servers obtain.[13] At the same time, this is very important information because without an exact time it is not possible to identify to whom (which computer system) a specific IP address has been assigned.

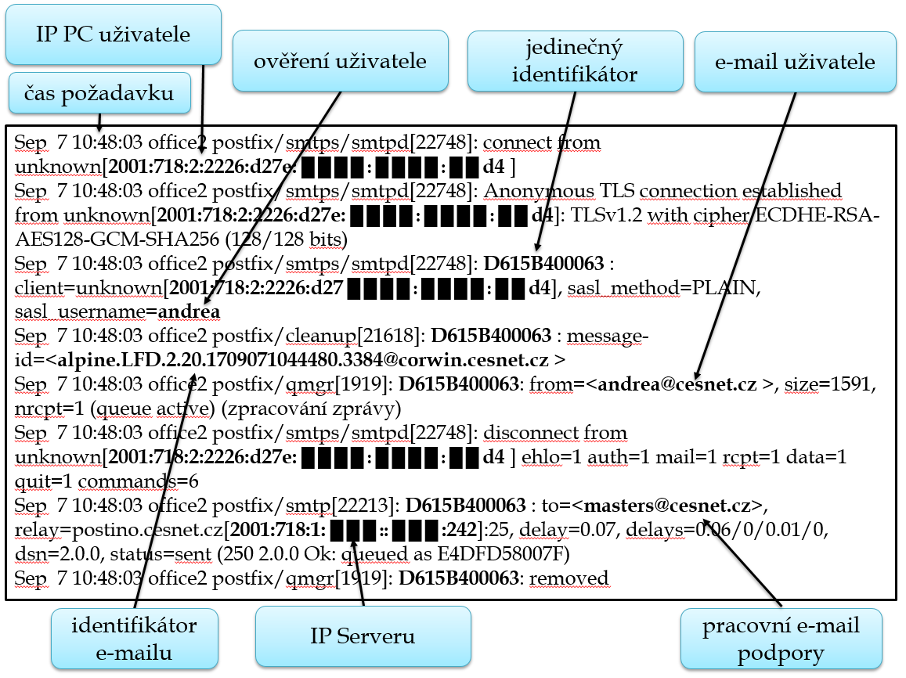

Another example showing the extent of data processing that can be considered personal data is the processing of personal data when sending email via SMTP.

|

IP PC uživatele |

IP address of a user’s PC |

|

čas požadavku |

request time |

|

ověření uživatele |

user authentication |

|

jedinečný identifikátor |

unique identifier |

|

e-mail uživatele |

user email |

|

(zpracování zprávy) |

(message processing) |

|

identifikátor e-mailu |

email identifier |

|

IP Serveru |

Server IP |

|

pracovní e-mail podpory |

support work email |

Figure: SMTP

If we again consistently focus on data (information) that are related to the data subject and are able to identify him/her, then personal data in this case will not be only the IP address of the connecting element and the IP address of the DHCP server.

The support work email could again be personal data if additional identifiers are assigned to it that are able to identify a natural person.

The key question is whether, in all processes that take place in computer systems (ICT elements) that are managed by an entity (natural or legal person), we are able to distinguish a situation where data are transferred purely between computer systems without relation to any natural person and when the natural person will already be involved in these processes as a data subject according to the GDPR.

We believe that, with specific exceptions, we will not be able to single out processes that take place without human interaction. Based on this assertion, the requirements of the GDPR should then be applied to all processes involving the manipulation of information that is relevant to the data subject and capable of identifying him or her. At the same time, it will be necessary to take sufficient security measures to sufficiently protect both the transmission system, computer systems and applications that work with such information and the information (or data) itself.

In addition to the above personal data, the GDPR defines specific categories of personal data that include data on:

- racial or ethnic origin,

- religion,

- political views,

- membership in trade unions or other organisations,

- sexual orientation,

- committing offences (crime/misdemeanour, etc.) and punishing them,

- genetic data (DNA & RNA),

- biometric data,

- health data.

6.2.3 Processing of personal data

According to Article 4 (2) of the GDRP, the processing of personal data means any operation or set of operations that is performed on personal data or on sets of personal data, whether or not by automated means, such as collection, recording, organisation, structuring, storage, adaptation or alteration, retrieval, consultation, use, disclosure by transmission, dissemination or otherwise making available, alignment or combination, restriction, erasure or destruction.

The protection of the data subject shall apply to the processing of personal data where such data are stored or entered in a register.[14]

However, according to the GDPR, processing cannot be understood as any handling of personal data. Processing of personal data must be considered as a more sophisticated activity that a controller performs with personal data for a certain purpose and does so systematically from a certain point of view.[15]

Among other things, activities performed by a natural person within the framework of a purely personal nature or activities performed exclusively in a household, and thus without any connection with professional or business activities, are excluded from the processing of personal data according to the GDPR.[16]

Article 5 (1) (a) of the GDPR sets out the principles for the processing of personal data. According to the GDPR, these principles include:

- lawfulness, fairness and transparency [Art. 5 (1) (a) of the GDPR] – a controller of personal data is obliged to:

- inform a data subject of the ongoing processing operation and its

purposes,

- inform a data subject about profiling and its consequences,

- inform a data subject, if personal data are obtained from him/her, whether he/she is obliged to provide these data and about the consequences of their possible non-provision,

- prove the existence of at least one legal reason for the processing of personal data,

- document:

- what, how, why it processes,

- consent and legal reason,

- the time for which it processes,

- guarantees and security measures taken.

- purpose limitation [Art. 5 (1) (b) of the GDPR] – personal data must be collected for

specified, explicit and legitimate purposes and not further processed in a

manner that is incompatible with those purposes,

- data minimisation [Art. 5 (1) (c) of the GDPR] – personal data must be commensurate and relevant to the purpose for which they are processed,

- accuracy [Art. 5 (1) (d) of the GDPR] – personal data must be accurate and, where necessary, kept up to date; every reasonable step must be taken to ensure that personal data that are inaccurate with regard to the purposes for which they are processed are erased or rectified without delay,

- storage limitation [Art. 5 (1) (e) of the GDPR] – personal data should be kept in a form that permits identification of data subjects for no longer than is necessary for the purposes for which they are processed,

- integrity and confidentiality [Art. 5 (1) (f) of the GDPR] – personal data must be processed in a manner that ensures appropriate security of the personal data, including protection against unauthorised or unlawful processing and against accidental loss, destruction or damage, using appropriate technical or organisational measures.

6.2.4 Security of personal data

One of the areas that the GDPR explicitly addresses is the issue of security of processing of personal data.

Article 32 of the GDPR states that, taking into account the state of the art, the costs of implementation and the nature, scope, context and purposes of processing as well as the risk of varying likelihood and severity for the rights and freedoms of natural persons, the controller (or processor) shall implement appropriate technical and organisational measures to ensure a level of security appropriate to the risk, including inter alia as appropriate:

- the pseudonymisation and encryption of personal data,

- the ability to ensure the ongoing confidentiality, integrity, availability and resilience of processing systems and services,

- the ability to restore the availability and access to personal data in a timely manner in the event of a physical or technical incident,

- a process for regularly testing, assessing and evaluating the effectiveness of technical and organisational measures for ensuring the security of the processing.

“In assessing the appropriate level of security account shall be taken in particular of the risks that are presented by processing, in particular from accidental or unlawful destruction, loss, alteration, unauthorised disclosure of, or access to personal data transmitted, stored or otherwise processed.”[17]

In determining the risk, it is necessary to take into account in particular the category of personal data that could be affected by the security breach, the nature of the security breach and the number of data subjects concerned. Higher risk is posed by “more sensitive” personal data (see e.g. special categories of personal data), a larger set of personal data, or data that can cause harm to the data subject or interfere with his or her rights.

According to Article 32 (4) of the GDPR, the controller and the processor shall take measures to ensure that any natural person acting under the authority of the controller or the processor who has access to personal data does not process them except on instructions from the controller, unless he or she is required to do so by European Union or Member State law.

6.2.5 Data Protection Impact Assessment (DPIA)

The Data Protection Impact Assessment (DPIA) is a tool to be used when a certain type of processing is likely, especially when using new technologies, taking into account the nature, scope, context and purposes of the processing, results in a high risk to the rights and freedoms of individuals. It is a tool that can help controllers identify potential risks of personal data processing and implement appropriate measures.

A data protection impact assessment should be carried out in the following cases:

- a systematic and comprehensive assessment of personal aspects relating to natural persons, based on automated processing, including profiling that determines decisions that produce legal effects in relation to natural persons or have a similarly serious impact on natural persons,

- processing of special categories of personal data (biometric data or data on criminal convictions and on criminal offences or related security measures),

- extensive systematic monitoring of publicly accessible premises,

- any other operation where the competent supervisory authority considers that the processing is likely to pose a high risk to the rights and freedoms of data subjects.

The data protection impact assessment should include:

- description of the intended processing operations,

- assessment of the necessity and adequacy of operations in terms of purpose (proportionality test),

- risk assessment for the rights and freedoms of entities,

- planned measures to address these risks, including guarantees, security measures, etc.

The GDPR itself also contains other institutions (e.g. pseudonymisation, requirements for erasure or portability of personal data, etc.) that may relate to activities carried out within information and communication systems and that require an appropriate level of security and protection.

It is important to identify the influence (impact) of the GDPR on an organisation, on its individual parts and processes. In fact, it is an audit where everywhere in an organisation or for the individual, personal data are processed in relation to the GDPR. Subsequently, the procedure is based on modifying or creating rules and processes (if necessary) both within an organisation and in relation to the data subject. At the same time, all these activities should respect the basic principles of security.

As with the implementation of security rules in general, when implementing the GDPR or other documents and recommendations, it should be kept in mind that there is no single rule, template, tool, solution or procedure applicable to each organisation or each situation.

It is necessary to adopt and implement your own solution in accordance with the GDPR.

It is necessary to individualise…

[1] [online]. Available from: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/CS/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:32016R0679&qid=1488972453767&from=CS

[2] ŠKORNIČKOVÁ, Eva. Jednoduchý test: Jak jste na tom s přípravou na GDPR? [online]. [cit. 10/11/2017]. Available from: https://www.gdpr.cz/blog/jednoduchy-test-jak-jste-na-tom-s-pripravou-na-gdpr/

[3] Cf. recital 6 of the GDPR

[4] EULA (End Users Licence Agreement) means the Terms of Service that allow the use of a service of a service provider. The EULA is a contract that is usually defined unilaterally by a service provider. However, a user is not limited in any way in his/her rights as he/she has the option of not using such unilaterally set terms of service. In the case of consent to the use of such services, it is generally possible to state that private law standards will be applied primarily.

The question is whether a user is really aware of what Terms of Service he/she has agreed to, when they become binding on him/her and what possible (legal) interference with his/her fundamental human rights and freedoms is such consent. Another important fact is that the service provided in this way may affect the rights and legitimate interests (e.g. IT security, trustworthiness of data, etc.) of third parties (e.g. employers, etc.) who have not explicitly agreed to use the service.

The sad fact remains that a very small percentage of users are willing to read the Terms of Service relating to a service provided.

[5] SLA (Service-Level Agreement) means an agreement entered into by and between a provider of a service and its user.

[6] This interaction can be monitored when using location and geolocation services (e.g. Google Maps, Waze, Map List, etc.) since a natural person assumes that the computer system will be able to locate him/her and display the most convenient route. Likewise, the interaction is expected, for example, for services enabling the sale and purchase of goods (e.g. Letgo – see recommended ads by geolocation or already purchased goods), restaurant and accommodation services (e.g. Tripadvisor, Booking.com, Airbnb, etc.), etc.

[7] For more details see KOLOUCH, Jan. CyberCrime. Prague: CZ.NIC, 2016, p. 78 et seq. and p. 109 et seq.

[8] See Article 3 of the GDPR – Territorial scope

[9] According to Article 4 (1) of the GDPR, a data subject is an identified or identifiable natural person. A subject may be identified:

- directly,

- indirectly (e.g. singling out, etc.).

[10] The recitals are provisions preceding the actual text of the GDPR and are in some cases an interpretation or, to some extent, an explanatory memorandum to the actual text of the regulation.

[11] For more details see: [online]. Available from: http://curia.europa.eu/juris/document/document.jsf?text=&docid=184668&pageIndex=0&doclang=cs&mode=lst&dir=&occ=first&part=1&cid=1403270

[12] On the concept of ISP itself, the rights and obligations of individual ISPs, see in more detail, for example, KOLOUCH, Jan. CyberCrime. Prague: CZ.NIC, 2016, p. 78 et seq. and p. 109 et seq.

[13] For more details see recital 30 of the GDPR

[14] See recital 15 of the GDPR

[15] For more details see Základní příručka k GDPR. [online]. [cit. 07/08/2018]. Available from: https://www.uoou.cz/zakladni%2Dprirucka%2Dk%2Dgdpr/ds-4744/archiv=0&p1=3938

[16] See recital 15 of the GDPR

[17] Article 32 (2) of the GDPR