Laws and regulations governing cybersecurity

3. Legal basis of ISP (internet service provider) activity

3.1. Regulation of ISP activities in the Czech Republic

The basic legal norm characterising the ISP activities in the Czech Republic is Act No. 480/2004 Coll., on Certain Information Society Services[1]. This act is an implementation of Directive (EU) 2015/1535 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 9 September 2015 laying down a procedure for the provision of information in the field of technical regulations and of rules on Information Society services.[2]

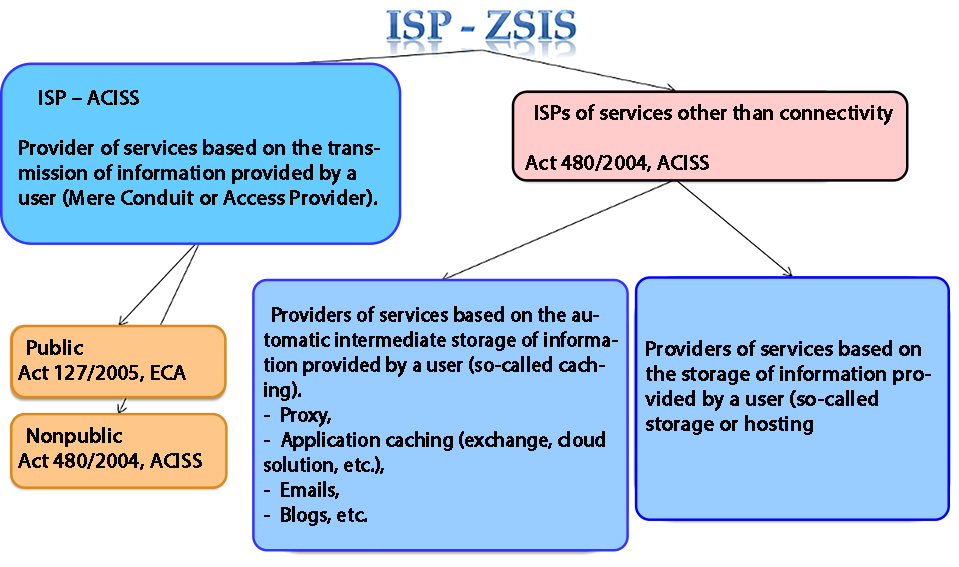

The Czech Act on Certain Information Society Services recognises the following three service providers, stipulating that a service provider is any natural or legal person who provides any of the information society services:[3]

1. Providers of services based on the transmission of information provided by a user (Mere Conduit or Access Provider).

2. Providers of services based on the automatic intermediate storage of information provided by a user (so-called caching).

3. Providers of services based on the storage of information provided by a user (so-called storage or hosting).

No person is excluded from the above definition. (It does not have to be, for example, a person doing business under another legal regulation.) However, if other special regulations apply to a provider (see e.g. one of the connection providers), they must also follow them.

[1] Hereinafter referred to as the Act on Certain Information Society Services or ACISS

[2] Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32015L1535&qid=1624364501265

[3] See Section 2 (d) of ACISS

Graphically, it is possible to show the listed providers (and the binding by individual legal regulations) as follows:

A recipient of an information society service is a user who can be any natural or legal person using the information society service, in particular for the purpose of seeking information or making it accessible.[1]

According to the Act on Certain Information Society Services, information society service means “any service provided by electronic means at the individual request of a user submitted by electronic means, normally provided for remuneration. A service shall be provided by electronic means if it is sent via an electronic communication network and collected by the user from electronic equipment for the storage of data.”[2]

The definition given in the Czech legislation is then directly based on Directive (EU) 2015/1535 of the European Parliament and of the Council [Article 1 (b)], which states that a service is “any information society service, i.e. any service normally provided for remuneration, remotely, by electronic means and at the individual request of a recipient of services.”

Four basic features of a service follow from this definition:

- it is provided by electronic means,

- it is provided at the individual request of a user,

- it is normally provided for remuneration,

- it is provided remotely (at a distance).

The concept of provision by electronic means is set out in Directive (EU) 2015/1535 of the European Parliament and of the Council in Article 1 (b) (ii), where it is defined as a service that is sent initially and received at its destination by means of electronic equipment for the processing (including digital compression) and storage of data. This service is entirely transmitted, conveyed and received by wire, radio, optical or other electromagnetic means. The Czech regulation uses a demonstrative list that states that it is mainly a network of electronic channels, electronic communication equipment, automatic calling and communication systems, telecommunications terminal equipment and electronic mail.[3]

An individual user request means that it must be an active activity by a user. Husovec states that it concerns cases where, for example, a user enters an address into the browser field (IE, Firefox, Chrome, etc.), thereby formulating a request to open the relevant page, or writes an SMS message. According to Husovec, a typical example of a service that is provided without an individual request is, for example, television broadcasting.[4]

The most problematic criterion for defining an information society service is that a service is provided for remuneration. The Czech regulation also copies the international regulation on this point and contains a provision “normally for remuneration”. In the environment of the Internet or other computer networks, there are a number of services that are provided “for free”. Husovec quite rightly argues that, under the term remuneration, it is possible to imagine a number of facts different from purely monetary performance.[5] It can be a performance that will take the form of a non-monetary nature, where an ISP obtains information about users in the form of personal, technical and other data, time spent using the service, offers a user advertising for other products, etc. However, even this condition should be interpreted more extensively according to Husovec, meaning that a potentially economic activity is carried out.[6]

Due to the fact that the term remuneration can mean really different possibilities (e.g. a thanks, visit to a site or link, financial or other payment) and due to the wording of the Act on Certain Information Society Services (see “normally for remuneration”), a conclusion can be reached that the activities of an information society service provider may also be provided free of charge.

The term remotely is defined by Directive (EU) 2015/1535 of the European Parliament and of the Council as a service that is provided without the parties being simultaneously present.[7]

In his monograph, Husovec also gives examples that demonstrate what can be considered an information society service. According to Directive 2000/31/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council, a number of activities that take place in the online world must be included under this concept. It can be online sales of goods, services that provide online information, commercial communication, or services providing tools for searching, accessing and retrieving data, services providing information transmission through a communication network, etc.

”The judicature of the Court of Justice of the EU has already directly or indirectly recognised, for example, the AdWords service (advertising service in Google search engine)[8], motor vehicle insurance services via the Internet[9], online sales of contact lenses[10], Internet connection[11], hotel reservations via email[12], travel agency services via email[13], eBay auction server[14] and traditional Google search.“ [15]

[1] See Section 2 (e) of ACISS

[2] See Section 2 (a) of ACISS

[3] See Section 2 (c) of ACISS

[4] For more details see HUSOVEC, Martin. Zodpovednosť na Internete podľa českého a slovenského práva. Prague: CZ.NIC, 2014, p. 100

[5] Ibidem, p. 98.

[6] Ibidem, p. 99.

[7] See Article 1 (b) (i) of this Directive.

[8] Decision Google France C-236/08 to C-238/08.

[9] Decision Bundesverband C-298/07.

[10] Decision Ker-Optika C-108/09.

[11] Decision Promusicae C-275/06 and Tele 2. C-557/07

[12] Decision Alpenhof C-144/09.

[13] Decision Pammer C-585/08.

[14] Decision L'Oreal v. Ebay 324/09.

[15] HUSOVEC, Martin. Zodpovednosť na Internete podľa českého a slovenského práva. Prague: CZ.NIC, 2014. ISBN: 978-80-904248-8-3, pp. 101–102.

3.1.1 Providers of services based on the transmission of information provided by a user (Mere Conduit or Access Provider)

From the point of view of the Act on Certain Information Society Services, such a provider may be any natural or legal person who is able to provide other entities (natural or legal persons) with the service of transmitting information (provided by users) via electronic communications networks or arranging access to electronic communications networks for the purpose of transmitting information.

Such a provider will not only be persons doing business in the field of connecting others to computer networks or the Internet (typically they will be persons registered in the Register of Entrepreneurs in Electronic Communications under the general authorisation)[1], but it will be any person providing or mediating transmission of information via electronic communications networks. It is therefore possible to imagine a situation where a connection provider according to this law will be a person who establishes and makes available to others, for example, Wi-Fi connection within a restaurant, apartment building, household, etc. This category will also include, for example, schools (typically universities that provide their students and teachers with connectivity within their network or to the Internet.). However, services based on the transfer of information also include, for example, the Skype application, ICQ, etc. We can very simply describe these providers as connection providers.

However, in order to define the individual rights and obligations of connection providers, these providers need to be divided into two groups, public and non-public. Both groups of connection providers are covered by the Act on Certain Information Society Services, but public connection providers are also covered by the Electronic Communications Act, which sets out further rights and obligations for these providers. The above-mentioned Register of Entrepreneurs in Electronic Communications according to the general authorisation administered by the Czech Telecommunication Office will help to determine whether the provider is included in which group.

[1] The database of entrepreneurs in electronic communications according to the general authorisation is available online: https://www.ctu.cz/vyhledavaci-databaze/evidence-podnikatelu-v-elektronickych-komunikacich-podle-vseobecneho-opravneni

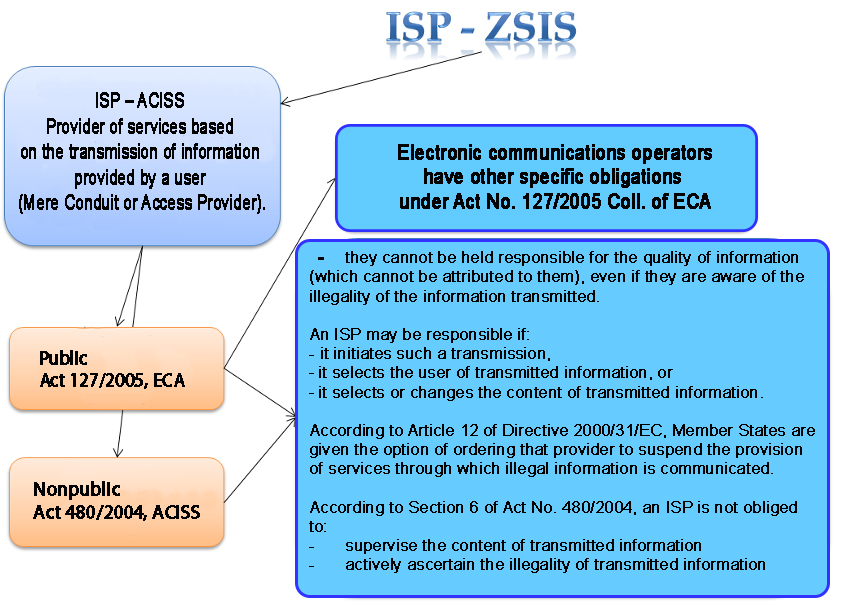

3.1.1.1 Rights and obligations of the provider of services based on the transmission of information provided by a user according to ACISS

The Act on Certain Information Society Services in the case of a connection provider limits as much as possible the responsibility of this entity for the transmitted information. However, special requirements and conditions are set for operators of electronic communications services. These conditions are set out in the Electronic Communications Act. Provisions of Article 12 of Directive 2000/31/EC allows Member States to order a provider to suspend the provision of services through which information is transmitted where said services unduly interfere with the rights of another. This option is one means of preventing infringements. The order to suspend the provision of services is usually issued by a court.

A connection provider can only be held responsible for the content of information if:

§ it initiates such a transmission,

§ it selects the user of transmitted information, or

§ it selects or changes the content of transmitted information.[1]

Pursuant to Section 6 of ACISS, a connection provider is not obliged to supervise the content of transmitted information or to actively ascertain the illegality of transmitted information. A provider cannot be held responsible for the quality of information (which cannot be attributed to it), even if it is aware of the illegality of transmitted information.[2]

3.1.1.2 Rights and obligations of the provider of services based on the transmission of information provided by a user according to Act No. 127/2005 Coll.

Public connection providers are also governed by Act No. 127/2005 Coll., on Electronic Communications[3]. This law defines some terms that it further uses. For the purposes of this monograph, these are in particular:

§ Electronic communications service [Section 2 (n) of ECA[4]]. According to Section 2 (n) ECA, this term means a service that is usually provided for a remuneration and is based on (wholly or mainly) the transmission of signals via electronic communications networks. This service does not include services offering content via electronic communications networks and services or exercising editorial supervision over content transmitted by networks and provided by electronic communications services. Furthermore, this service does not include information society services that are not based wholly or mainly on the transmission of signals over electronic communications networks.

§ Publicly available electronic communications service [Section 2 (o) of ECA]. This service is an electronic communications service that no one is excluded from using beforehand.

Non-exclusion means the possibility of entering into a contract with a business entity providing a publicly available electronic communications service. It is important that this service is open to a wide range of people, none of whom is excluded beforehand. The opposite of such a service can be, for example, membership in various associations, chambers, or, for example, the status of a school student.

§ A business entity providing or authorised to provide a public communications network or associated facilities is referred to by this act as an operator [Section 2 (e) of ECA].

§ Subscriber [Section 2 (a) of ECA] is anyone who entered into a contract for the supply of such service with a business entity providing publicly available electronic communications services. User [Section 2 letter n) ZoEK] is anyone who uses or requests a publicly available electronic communications service.

The Electronic Communications Act introduced, on the basis of Directive 2006/24/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 15 March 2006, on the retention of data generated or processed in connection with the provision of publicly available electronic communications services or of public communications networks and amending Directive 2002/58/EC [5], the obligation to preventively retain traffic and location data[6] on electronic communications. This obligation only applies to a business entity providing or authorised to provide a public communications network or associated facilities.

The purpose of the Data Retention Directive was to harmonise Member States’ rules on the obligation of providers of publicly available electronic communications services or public communications networks to retain traffic and location data so that they can be provided to Member States’ competent authorities for prevention, investigation, detection and prosecution of serious crime, such as terrorism and organised crime.

The scope of the directive has been defined in the area of traffic and location data on legal and natural persons and on related data that are necessary to identify the subscriber or registered user.

This directive did not apply to the content of electronic communications or to information required when using an electronic communications network.

Under the directive, the Member States were required to ensure that telecommunications data were retained for a minimum of six months and a maximum of two years from the date of communication. The directive has been transposed in various forms into the legal systems of the EU Member States. However, since its inception, there have been conflicts of opinion on the directive as such. Opponents argued that the directive disproportionately interferes with fundamental human rights and freedoms, in particular by essentially mandating the widespread collection of information on individual users. It was further argued that the directive (in such a general form) would not be able to pass the proportionality test.

The proportionality test is a standard legal instrument of both international courts and constitutional (national) courts when assessing the conflict of provisions of the legal order seeking to protect a constitutionally guaranteed right or public interest with another fundamental right or freedom. The proportionality test includes three criteria for assessing the admissibility of an intervention:

- The principle of suitability (fitness for purpose), according to which the measure in question must be capable of achieving the intended objective in general, which is the protection of another fundamental right or public good.

- The principle of necessity, which stipulates the use of only the most environmentally friendly means to achieve the desired purpose (interference with fundamental rights and freedoms) from several possible means.

- The principle of proportionality (in the narrower sense), which seeks to prevent harm to a fundamental right disproportionate to the intended objective, i.e. measures restricting fundamental human rights and freedoms must not, in the event of a conflict between a fundamental right or freedom and the public interest, exceed, by their negative consequences, the positives of the public interest in these measures.

The Data Retention Directive and its national transposition have become the subject of constitutional lawsuits in some EU countries. The decisions especially of the constitutional courts of Romania (2009), Germany (2010) and the Czech Republic (2011) must be mentioned among the most crucial. I will focus on court decisions in Germany and the Czech Republic.

The Federal Constitutional Court of Germany resolved a conflict between freedom and security (based on the Data Retention Directive) and ruled in favour of individual freedom. On 2 March 2010, the court ruled that the mass retention of data on telephone and data transmissions was unconstitutional in Germany.

The court responded to a mass complaint from 35,000 citizens seeking the repeal of a 2008 law ordering telecommunications companies to archive records of telephone calls and email communications for six months for investigative purposes. The Federal Constitutional Court repealed the contested regulations on the grounds that they were unconstitutional. It further stated that the obligation to retain data to the specified extent is not entirely unconstitutional from the outset, but there is no legal regulation corresponding to the principle of proportionality. According to the court, the contested regulations were not in line with constitutional requirements for data security, the purpose of the use of the data (and the transparency of the use of the data) was not clearly defined, and legal protection was not sufficiently ensured.

The court stated that “the exercise of the fundamental rights and freedoms of citizens (here the secrecy of messages transmitted by electronic means of communication) must not be completely monitored, documented and registered by the state; this belongs to the constitutional legal identity of the Federal Republic of Germany, the preservation of which the republic must stand in at European and international level.”[7]

In the Czech Republic, the Data Retention Directive was implemented before its entry into force within the EU. (In the EU, it was implemented on 15 March 2007, with a requirement for transposition by 15 September 2007. In the Czech Republic, it was implemented in Section 97/3 of ECA, with effect from 1 May 2005.) A constitutional complaint was also filed in the Czech Republic, specifically by the association Iuricum Remedium, which was supported by a group of 51 deputies. This complaint was filed with the Constitutional Court in March 2010. In 2011, the Constitutional Court ruled and fully granted the petition for complete annulment of the relevant passages of the Electronic Communications Act (specifically Section 97 (3) and (4) and Implementing Decree No. 485/2005 Coll., on the Extent of Traffic and Location Data and the repeal of the provisions of the Criminal Procedure Code.[8] The Court stated as follows: “The Constitutional Court found that the contested legislation violates constitutional limits because it does not meet the requirements of the rule of law and contravenes the requirements of restricting the fundamental right to privacy in the form of the right to informational self-determination within the meaning of Art. 10 (3) and Art. 13 of the Charter, which follow from the principle of proportionality.”

Legislators in the Czech Republic responded to the objections of the Constitutional Court of the Czech Republic, and new legislation that continues to allow widespread retention of traffic and location data in the Czech Republic was adopted as it respects the aforementioned proportionality test, in particular by clearly declaring the range of entities (authorised to request traffic and location data) and the purpose for which the data may be requested.

At the same time, measures have been taken ordering business entities to adopt such rules under the Electronic Communications Act to ensure that traffic and location data are of the same quality and subject to the same security and protection against unauthorised access, alteration, destruction, loss or theft or other unauthorised processing or use as data according to Section 88 of ECA.[9]

The maximum length for which these data can be retained has also been set. It is currently 6 months. After expiration of this period, a legal or natural person who retains traffic and location data is obliged to delete them, unless they have been provided to authorities authorised to use them under special legislation or unless otherwise provided by law (Section 90 of ECA). Furthermore, an obligation was established to ensure that the content of messages is not retained and further handed over during the retention of traffic and location data (Section 97 (3) of ECA).

At the same time, the Criminal Procedure Code emphasises the principle of subsidiarity (especially Sections 88 and 88a of Act No. 141/1961 Coll., on Criminal Court Proceedings: “if the intended purpose cannot be achieved otherwise or if its achievement would be significantly more difficult”). The guarantee of minimum inteference with the fundamental human rights in these cases is given, among other things, by the fact that the order to issue traffic and location data is issued by a judge on the proposal of the public prosecutor.

Who is therefore entitled to request the release of traffic and location data and under what conditions in the Czech Republic? Pursuant to Section 97 (3) of ECA, a legal entity or natural person who retains traffic and location data shall make them available without delay upon request to:

a) the law enforcement authorities for the purposes and in compliance with the conditions stipulated by a special legal regulation[10],

b) the Police of the Czech Republic for the purposes of initiating a search for a specific wanted or missing person, identifying a person of unknown identity or the identity of a found corpse, preventing or detecting specific threats in terrorism or screening a protected person and if the conditions stipulated by a special legal regulation are met[11],

c) the Security Information Service for the purposes and in compliance with the conditions stipulated by a special legal regulation[12],

d) Military Intelligence for the purposes and in compliance with the conditions stipulated by a special legal regulation[13],

e) the Czech National Bank for the purposes and in compliance with the conditions stipulated by special legislation61)[14].

Within the European Union, the Court of Justice of the EU (on 8 April 2014) issued a verdict following the previous opinion of [15]its Advocate General Pedro Cruz Villalón[16], in which it annulled the relevant Data Retention Directive (2006/24/EC).

“By today’s judgment, the Court of Justice declares the directive invalid.”

“As the Court of Justice has not limited the temporal effects of the judgment, the declaration of invalidity is effective from the date on which the directive enters into force.”

In particular, the Court of Justice of the EU criticised the fact that “the EU legislature has exceeded the limits set by the requirement of compliance with the principle of proportionality by adopting the Data Retention Directive.”

The decision to maintain or repeal the existing legislation governing the retention of traffic and location data in the EU Member States is entirely up to the relevant national authorities, and the European Union itself does not intend to recommend or provide any guidance on how to act.[17]

How to approach the widespread retention of traffic and location data? Personally, I believe that, in cyberspace, it is not possible to reconstruct events that have taken place in the past other than by retention of traffic and location data. Cyberspace and ICT, which allow a very fast change in the topology of the network, services, etc. technologies that allow the acquisition of several different identities within seconds, in fact, do not allow any other option.

I am aware that the widespread retention of traffic and location data interferes with my fundamental rights and freedoms. However, by adopting the concept of a social contract and relinquishing part of my rights and freedoms in favour of an authority (in our case the state) to protect myself and my rights, I have, in fact, no other choice. I believe that, if we want to effectively check and investigate cybercrime, cyberattacks and other negative phenomena that are taking place in cyberspace, we cannot do that without this tool. The issue we should address should not be: “How to limit the collection of data and information about people in cyberspace (because this happens at completely different levels) and thus limit the state’s ability to address negative phenomena in cyberspace?” The issues that are completely legitimate and that should be addressed are: “How to set the rules, to whom and under what conditions to allow access to the data, what happens to the data, for what purposes they can be used, etc.”

Personally, I believe that similar data should not only be retained by public service providers but by all ISPs that provide a service. My opinion is grounded on the following reasons.

Firstly, I believe that services other than those based on the provision of connections are and will continue to be the majority of services in cyberspace. A user thus stops addressing the issue of who connects him/her and how and is primarily engaged in services that may, for example, take the form of a virtual connection to various virtual environments. Thus, it is not the physical connection itself what will be significant but the connection between the individual services.

The second reason is the fact that the vast majority of providers of these services already retain not only traffic and location data but a number of other data that users allow them to retain on the basis of the Terms of Service agreed by an end user with regards to an ISP.

The last reason is an ISP’s own protection from users. A service provider must respect the law, and it is in its best interest to retain data that could potentially exempt it from liability, for example, for damage or other harm.

An Advocate General has recently commented on the retention of traffic and location data[18]. He noted that data retention is in many cases the only effective tool for dealing with security risks and serious crime. At the same time, he formulated requirements for its proportional implementation in the legal systems of the Member States.

Graphical representation of the division of connection providers and some of their rights and obligations

[1] These three options make a connection provider essentially liable only if it is such an entity that actively sends or otherwise manipulates transmitted information.

[2] Cf. Article 12 of Directive 2000/31/EC and the provisions of Section 3 (1), (2) of Act No. 480/2004 Coll.

[3] Hereinafter referred to as the ECA

[4] Hereinafter referred to as the ECA

[5] Hereinafter referred to as the Data Retention Directive. The term data retention means the widespread storage of traffic and location data at connection providers (in the Czech Republic at providers under the Electronic Communications Act).

[6] See Section 97 (4) of ECA.

Traffic and location data are mainly data leading to the tracing and identification of the source and recipient of a communication, as well as data leading to the determination of the date, time, method and duration of the communication.

The scope of traffic and location data, the form and manner of their transmission to bodies authorised for use pursuant to a special legal regulation (see Section 97 (3) of ECA) and the manner of their deletion shall be determined by a statutory legal instrument. The statutory instrument is Decree No. 357/2012 Coll., on the retention, transfer and deletion of traffic and location data.

[7] German Federal Constitutional Court rejects data retention law. [online]. [cit.16/07/2016]. Available from: https://edri.org/edrigramnumber8-5german-decision-data-retention-unconstitutional/

See also e.g.:

National legal challenges to the Data Retention Directive. [online]. [cit.16/07/2016]. Available from: https://eulawanalysis.blogspot.cz/2014/04/national-legal-challenges-to-data.html

Data retention unconstitutional in its present form. [online]. [cit.16/07/2016]. Available from: https://www.bundesverfassungsgericht.de/SharedDocs/Pressemitteilungen/EN/2010/bvg10-011.html?nn=5404690

German Bundestag Passes New Data Retention Law. [online]. [cit.16/07/2016]. Available from: http://www.gppi.net/publications/global-internet-politics/article/german-bundestag-passes-new-data-retention-law/

[8] See Constitutional Court ruling Pl. ÚS 41/11, as at 22/03/2011. Shromažďování a využívání provozních a lokalizačních údajů o telekomunikačním provozu. [online]. [cit. 24/08/2016]. Available from: http://nalus.usoud.cz/Search/ResultDetail.aspx?id=69635&pos=1&cnt=4&typ=result

[9] For more details see Section 88a of ECA

[10] Act No. 141/1961 Coll., on Criminal Court Proceedings (Criminal Code), as amended.

[11] Act No. 273/2008 Coll., on the Police of the Czech Republic, as amended.

Act No. 137/2001 Coll., on Special Protection of a Witness and Other Persons in Connection with Criminal Proceedings and on Amendments to Act No. 99/1963 Coll., the Code of Civil Procedure, as amended.

[12] Sections 6 to 8 of Act No. 154/1994 Coll., on the Security Information Service, as amended.

[13] Sections 9 and 10 of Act No. 289/2005 Coll., on Military Intelligence.

[14] Act No. 15/1998 Coll., on Supervision in the Area of the Capital Market and on Amendments to Other Acts, as amended.

[15]Opinion of Advocate General Pedro Cruz Villalón Case C-293/12 and C-594/12. [online]. [cit.15/07/2016]. Available from: http://curia.europa.eu/juris/document/document.jsf?text=&docid=145562&pageIndex=0&doclang=CS&mode=req&dir=&occ=first&part=1&cid=727954

[16] The Court of Justice of the European Union. Press release No. 54/14, dated 8 April 2014. Judgment in joined cases C-293/12 and C-594/12. [online]. [cited 15/07/2016]. Available from: http://curia.europa.eu/jcms/upload/docs/application/pdf/2014-04/cp140054cs.pdf

[17] PETERKA, Jiří. Uchovávat provozní a lokalizační údaje nám už EU nenařizuje. My to v tom ale pokračujeme. [online]. [cit. 10/11/2015]. Available from: http://www.earchiv.cz/b14/b0428001.php3

[18] Opinion of the Advocate General SAUGMANDSGAARD ØE, from 19/07/2016. In joined cases C-203/15 and C-698/15. [online]. [cited 10/8/2016]. Available from: http://curia.europa.eu/juris/document/document.jsf?text=&docid=181841&pageIndex=0&doclang=EN&mode=req&dir=&occ=first&part=1&cid=111650

3.1.2 Providers of services based on the automatic intermediate storage of information provided by a user (so-called caching)

Caching is based on the transfer of information, during which it is automatically temporarily stored. Subsequently, this information is transmitted to the recipients of the service at their request.

“Caching is basically a special arrangement of the mere conduit service as it also includes transmission with temporary intermediate storage of information. The only difference in which the caching service could deviate from the scope of a broadly conceived mere conduit is that storage during transmission is performed for a “period longer than is reasonably necessary for transmission”.[1]

Husovec also very aptly describes caching services on the example of a proxy server or caching browser, which speed up the loading of web pages. A recipient of the service is an owner of a daily news website (so-called primary recipient), whose images are saved by a caching provider on a geographically closer computer (e.g. in Europe) so that he does not have to constantly access the computer where the original website is stored (e.g. Africa). Consequently, the overall page load (in Europe) is sped up. A user who visits the website and is another recipient of the service (so-called secondary recipient), thus, on the basis of an individual request addressed to the caching service provider, obtains an image from its computer and is not forced to “travel” to the original computer.[2]

Caching providers are not relieved of responsibility for the quality of information if they violate the standard or agreed technical conditions of caching.[3]

According to Section 4 of ACISS, a caching provider is responsible if it:

a) changes the content of information,

b) does not meet the conditions for access to information,

c) does not comply with the rules on updating information that are generally recognised and used in the sector concerned,

d) exceeds the permitted use of technology generally recognised and used in the industry to obtain usage data; or

e) shall not take immediate action to remove or deny access to information it stores as soon as it finds that the information has been removed from or accessed from the network at the point of transmission or has been ordered by a court to withdraw or deny access to it.

A caching provider is not obliged to actively search for facts and circumstances pointing to the illegal content of information or to supervise the content of information transmitted or stored by it.

[1] see HUSOVEC, Martin. Zodpovednosť na Internete podľa českého a slovenského práva. Prague: CZ.NIC, 2014, p. 133

[2] Ibidem, p. 133.

[3] Cf. Article 13 of Directive 2000/31/EC and the provisions of Section 4 of ACISS

Cf. POLČÁK, Radim. Právo na internetu. Spam a odpovědnost ISP. Brno: Computer Press, 2007, p. 58

3.1.3 Providers of services based on the storage of information provided by a user (so-called storage or hosting)

Providing storage or hosting means making storage (space) available to a user so that he/she can place data there. Storing information or data, unlike mere conduit or caching, is not only temporary. Hosting services include:

a) Webhosting (Active 24, Ignum, Zoner, etc.)

b) Cloud storage enabling storage of any files and data (Dropbox, iCloud, Microsoft OneDrive, ownCloud, etc.)

c) File storage (Rapidshare, DropBox, etc.)

d) Video storage (YouTube, etc.)

e) Audio file storage (iTunes, etc.)

f) Internet auction services (eBay, etc.)

g) Blogs, forums, discussion chats, etc.

h) Social media (Facebook, Twitter, etc.).

The above list is not final. A number of other services can be provided within a hosting.

For hosting providers, the situation with their possible legal liability is the most complicated.[1] Again, it is based on the provisions of Directive No. 2000/31/EC, the recommendations of which were adopted by the Czech legislator in Section 5 of ACISS. This provision stipulates at least a provider’s unintentional negligence[2] in relation to an unlawful content of information stored by the provider. However, the legislator does not oblige providers to actively search for illegal information of users[3] (because in many cases it would in effect be an interference with the fundamental rights and freedoms guaranteed by the Charter – e.g. Article 13) or to supervise the content of transmitted or stored information.

According to Section 5 (1) of ACISS, a hosting provider shall be responsible if it:

a) could, with regard to the subject of its activity and the circumstances and nature of the case, know that the contents of the information stored or action of the user are illegal, or

b) having demonstrably obtained knowledge of an illegal nature of the information stored or illegal action of the user, failed to take, without delay, all measures, that could be required, to remove or disable access to such information.

A hosting provider shall always be responsible for the content of the information stored if it exerts, directly or indirectly, decisive influence on the user’s activity.[4]

For the purposes of this monograph, only certain aspects related to information society service providers have been selected, in particular with regard to the usability of information in the detection and investigation of cybercrime and cyberattacks.

[1] Cf. Article 14 of Directive 2000/31/EC and the provisions of Section 5 of ACISS

[2] Cf. provisions of Section 16 (1) (b) of the Criminal Code.

[3] Cf. Article 15 of Directive 2000/31/EC and the provisions of Section 6 of ACISS

[4] Section 5 (2) of ACISS