Laws and regulations governing cybersecurity

2. Responsibility in cyberspace

2.2. Scope of the law in Cyberspace

Cyberspace is open and easily accessible to all, “… there are no special laws, and it is necessary to follow generally binding standards.”[1]

The indisputable fact is that the implementation of an ever-increasing number of social as well as economic relations is moving into the environment of information networks. Thus, the need for a certain legal regulation of such conduct arises. Due to the delocalisation of legal entities in different countries around the world, the question is what legal system (if any) will apply to any acts (or offences) committed on the Internet.

It is therefore necessary to primarily address two issues. Firstly, whether the law applies on the Internet and, if so, what legal norms apply. Secondly, how this right can be exercised, including possible sanctions or other measures. An example of a difficult application of the law is a case in 2005, when a player of an online game “The Legend of Mir 3” killed another player in China for stealing a virtual weapon. There is a trade in virtual commodities among the players of this game, as well as a loan system. This is especially evident when some players are friends, but it is not a condition that they know each other from the real world. It was a loan that caused the murder. A player named Qui Chengwei lent a virtual sabre, the “Dragon sabre”, to his virtual friend Zhu Caoyuan. However, Zhu succumbed to the allure of easy money and sold the weapon for 7,200 yuan (which is about 19,000–20,000 CZK) at an online auction. After Qui learned of the sale, he turned to the police and reported the theft of the virtual sabre. The police refused to handle the case, stating that virtual property (of essentially non-existent items) is not covered by law. Qui lost patience, attacked Zhu at his house and stabbed him to death.[2]

It is obvious that this is a very extreme case, but it appropriately demonstrates that the virtual world is not detached from the real world. Therefore, the issue of legal liability in it must be addressed.[3] In fact, since the beginning of the development of the Internet, there has been a conflict between the technical and legal worlds. From a technical perspective, the Internet is logically designed with a clear hierarchy and structure. However, the law, especially local law, has often injected “chaos” into this logic. The term “chaos” perhaps most aptly describes the efforts of legislation to regulate this purely technical world because, in cyberspace, a user has a wide range of options to “circumvent” a certain ban or restriction. In the following examples, I will try to demonstrate the interaction of the real and virtual world.

LICRA vs. Yahoo

One of the first cases relating to the applicability of the law on the Internet occurred in France in 2000. In February 2000, Marc Knobel (a French Jew who dedicated his life to fighting Nazism) visited the auction site www.yahoo.com and found that the server offered a number of Nazi-related items or items related to the German armed forces from World War II on its websites. After this discovery, Marc Knobel turned to Yahoo! Inc. requesting to block this site. Yahoo! Inc., however, did not comply with his request. On 11 April 2000, Marc Knobel, through LICRA (Ligue Internationale Contre Le Racisme et l'Antisémitisme) brought an action against Yahoo! Inc. in a French court for violating French law since the promotion and support of Nazism on television, on radio and in writing is prohibited in France. Yahoo! Inc. defended itself by claiming that the servers on which the auction portal operates are physically located in the United States, so French law cannot be applied to hardware and websites operated in the United States. The defence further argued that the content of the websites is primarily intended for US residents, to whom the First Amendment guarantees freedom of expression. Any attempt to remove this website would then be inconsistent with this amendment.

However, LICRA pointed out that, if Yahoo! Inc. does business in France, it has to respect the laws of France, and the Internet is no exception. Yahoo! Inc. responded to this argument that it is not able to determine where their customers are logging in to the auction portal. Therefore, if they removed the websites in question, not only would they not respect the First Amendment, but they would prevent access for all users, regardless of borders. This would make French law de facto global law. On 22 May, 2000, Judge Jean-Jacques Gomez ordered the company to block French users from accessing US auction websites with Nazi memorials. He justified his decision, inter alia, by saying that Yahoo! Inc. can identify French users so well that they can place advertisements in French on the websites they visit. The judge gave Yahoo! Inc. 90 days to install keyword-based filtering system on the Yahoo! Inc. French websites. “Judge Gomez stated in the reasoning that it is possible to block up to ninety percent of French users from accessing the websites in question. The technical solution that Yahoo! has to come up with on the basis of the judgment will be assessed by a three-member international panel. His earlier finding states that up to 70 percent of users can be unblocked by their Internet Service Provider (ISP) designation and another 20 percent by tracking search engine keywords on Yahoo!.“[4]

Greg Wrenn, Yahoo! Inc. lawyer, said: “Whenever the word Hitler is mentioned on a page commemorating Holocaust victims, the page will be closed automatically. It is not possible to talk about an effective judgment at all because in fact it is not possible to meet it.”

The technical problems at that time were, and still are to this day, in that only what can be clearly defined can be filtered (words such as Nazi, Heil Hitler, etc.). But the filter is not able to detect all possible versions of unwanted material (e.g. N_A_Z_I, H3Il HiT_L3R, etc.). These differences can be recognised by natural persons (e.g. employees of a particular ISP), who then delete the page; however, an operator of a reprehensible forum or auction can simply change the address and continue its activities.

Yahoo! Inc. waived its appeal against the French court’s judgment and began blocking French users from websites offering objectionable content. However, Yahoo! Inc. also applied to the court[5] with local jurisdiction in the United States for a declaratory judgment that would exclude the jurisdiction of the French court over the American company. That court upheld the view of Yahoo! Inc. that the enforcement of the French decision in the United States was unconstitutional. LICRA appealed against that judgment. The US Court of Appeals responded by denying its jurisdiction over LICRA organisations. In 2006, the case went to the US Supreme Court[6], which refused to consider the case in the end. Thus, US court rulings were more in favour of Yahoo! Inc. However, it eventually voluntarily decided to completely remove websites offering Nazi-themed items from its servers, not only in France.

Gutnick vs. Dow Jones

Joseph Gutnick (an Australian diamond businessman) read an article about himself in an online edition of Barron’s[7] newspaper in 2000, which he considered defamatory. Gutnick filed a defamation lawsuit against Dow Jones in an Australian court. Dow Jones used similar arguments as Yahoo! Inc. in its dispute with LICRA. The argument was based primarily on the fact that the printed version of the newspaper is primarily intended for the US market, so the case cannot be covered by Australian law.

Despite this argument, the Australian court ruled[8] in 2002[9] as follows: “Since the material (article) is also available in Australia, the place where Gutnick is best known, the defamation can do him the most harm. Dow Jones is required to pay Gutnick compensation.” The court said it would not consider whether the Internet has boundaries or not, taking into account in particular where the content was available, not where it was published. The court also stated that everyone has the right to legal protection against similar conduct or other attacks. In its judgment, the Australian court also noted the reality of the cross-border nature of the Internet, which corresponds to the extensive exercise of jurisdiction.

GoDaddy

GoDaddy[10] is the US majority registrar of Internet domains. In 2016, it manages more than 61 million Internet domains, making GoDaddy the largest domain registrar. Registering a domain with this ISP is very simple and affordable. At the same time, due to the company’s location in the US, users are provided with legal protection for their personal data and data listed on a domain registered under GoDaddy, provided that users do not violate US law. For this reason, domains registered with GoDaddy are very often used by, for example, extremist, racist and other groups or users. These users then depend on US constitutional law and the First Amendment to the US Constitution:

“Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the government for a redress of grievances.”[11]

The problem in addressing cybercrime with the above content is to prove the reality of the threat or crime so that it is not a violation of the First Amendment to the Constitution.

Second Life (and “child” porn).

Second Life is a 3D virtual environment developed by Linden Lab. This environment allows you to create your own avatars and use them to interact with others, with the possibility to generate profit. Second Life is divided into two virtual worlds according to the age of a user.[12] Users are able to change their identity and modify the appearance of the avatar according to their ideas. In 2007, the German station ARD and subsequently CNN drew attention to the existence of a “paedophile island.”[13]

This report points to the fact that some MainGrid users (i.e. users over the age of 18) created avatars in the form of a child and others pretended to be adults. As part of the mutual interaction, avatars of children were abused by adult avatars. Law enforcement authorities in Germany launched an investigation because possession of virtual child pornography is a criminal offence under German criminal law.[14] Linden Lab cooperated with the German authorities in identifying the users and owners of the virtual plots on which the virtual child pornography took place. In the Federal Republic of Germany and the United Kingdom, the conduct in question was punishable by criminal law, but in the United States such conduct was not prosecutable.

At present, there is no state in the world that would waive the right to punish an infringement that affects the interests it protects.

|

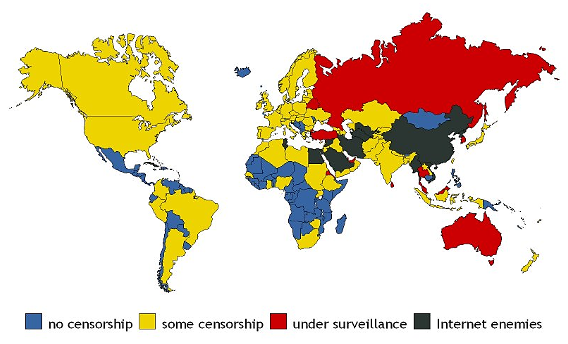

Figure 1 – Division of states according to Internet censorship |

The map presented (see Figure 1)[15] shows that most countries in the world have adopted legal instruments that affect the Internet or the services provided.

From a user’s point of view, it must be stated that the principle of territoriality in connection with the Internet loses its meaning because he/she can be located anywhere in the world at any time, without a user having to know where the server with which he/she is communicating is located. From this point of view, the Internet is global and knows no boundaries.

”It is true that a physical location of certain information can be traced at any given time – but the location is often random, very short-term and usually completely irrelevant to the information as such and its legal effect."[16]

The law should keep pace with the virtual world, but unfortunately this does not always work as states (closed in fixed territories) often lack the means to effectively enforce law within cyberspace.[17] Basically, there are two ways to address this problem. One possibility is to respect the principles of territoriality of states as they are set today. This approach would then essentially mean that, if someone interfered with the rights that the state guaranteed to protect, it would have to wait until the attacker is in the physical jurisdiction of the state[18], or the attacker would have to use international legal aid.

The second option is to create special legislation, the so-called Internet jurisdiction, which would apply to the online world. The question is how this new right would be adopted by individual countries. Personally, I believe that, under the current conditions, it is not possible to unite all branches of law worldwide (civil, commercial, criminal, administrative, etc.), in which the Internet intervenes in some way. I base my assertion on the fact that the Convention on Cybercrime, which defines the basic groups of crimes that should be prosecuted in cyberspace, was adopted in 2001, but as of 1 August 2016, only 49 countries had ratified it.

Given the global nature of the Internet, it also seems to be problematic to determine:

1. applicable law (under which state’s law the potential litigation will be decided),

2. authority empowered to issue a decision,

3. authority which may enforce or directly execute a decision.[19]

In addition to classical legal norms, defining authorities participate in the creation of the law or rules on the Internet by creating defining standards.[1] SMEJKAL, Vladimír. Internet a §§§. 2nd updat. and ext. ed. Prague: Grada, 2001, p. 32

[2]Cf. HAINES, Lester. Online gamer stabbed over “stolen” cybersword. [online]. [cit.03/10/2006]. Available from: http://www.theregister.co.uk/2005/03/30/online_gaming_death/

[3] Cf. Decision of the Supreme Court 4 Tz 265/2000, as of 16/01/2001. [online]. [cit.13/03/2008]. Available from: http://www.nsoud.cz/Judikatura/judikatura_ns.nsf/WebSearch/B82A96F8E1B60D3AC1257A4E00694707?openDocument&Highlight=0

[4] ŠTOČEK, Milan. V Hitlerově duchu proti Hitlerovi. [online]. [cit.10/07/2016]. Available from: http://www.euro.cz/byznys/v-hitlerove-duchu-proti-hitlerovi-814325

[5] United States District Court for the Northern District of California in San Jose

[6] United States Supreme Court

[8] High Court of Australia

[9] Judgement [2002] HCA 56 as at 10 December 2002, [online]. [cit.24/03/2014]. Available from:

[11] First Amendment. [online]. [cit.10/07/2016]. Available from: https://www.law.cornell.edu/constitution/first_amendment Author’s translation

[12] MainGrid – intended for users from the age of 18; TeenGrid – intended for the age group from 13 to 18.

[13] For more details see: CNN on pedophile sex in Second Life. [online]. [cit.18/06/2009]. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AQM-SiiaipE

[14] Second Life 'child abuse' claim. [online]. [cit. 16/06/2009]. Available from:

[15] Internet censorship. [online]. [cit.10/08/2016]. Available from: http://www.deliveringdata.com/2010_10_01_archive.html

[16] POLČÁK, Radim. Právo na internetu. Spam a odpovědnost ISP. Brno: Computer Press, 2007, p. 7

[17] Cf. statements in the framework of the Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace.

Cf. THOMAS, Douglas. Criminality on the Electronic Frontier. In Cybercrime. London: Routledge, 2003, p. 17 et seq.

Cf. JOHNSON, David R. and David POST. The Rise of Law in Cyberspace. [online]. [cit.10/07/2016]. Available from: http://poseidon01.ssrn.com/delivery.php?ID=797101088103069021099122095084084095061040041017050027018013071117008115007025117112101013061121056036119084118089028085067043023001058093120070084069085089012000019127120091078115090125017120030014000101095031109003094069069113114112102&EXT=pdf

[18] An example of this approach may be the case where a user from the Czech Republic, for example, will publicly and repeatedly attack a country on the Internet (e.g. for non-compliance with human rights in said country, etc.), or will carry out other activities that are illegal in the targeted country (though it is not illegal in the Czech Republic). If such a user decides at any time in the future to visit the country against which he/she has acted against, the country’s territorial law may apply to him/her when crossing the borders into that country.

[19] POLČÁK, Radim. Právo na internetu. Spam a odpovědnost ISP. Brno: Computer Press, 2007, p. 7